CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | FEBRUARY 2019

Suspicious Activity Reports

on Elder Financial

Exploitation: Issues and

Trends

Office of Financial Protection for Older Americans

1 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Table of contents

Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 3

Key findings ............................................................................................. 3

1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 6

2. Background ......................................................................................................... 8

3. Trends in SAR submissions .......................................................................... 11

SAR filings on elder financial exploitation quadrupled from 2013 to 2017 .. 11

Money services businesses have filed an increasing share of EFE SARs .. 12

4. Monetary losses reported in EFE SARs ...................................................... 14

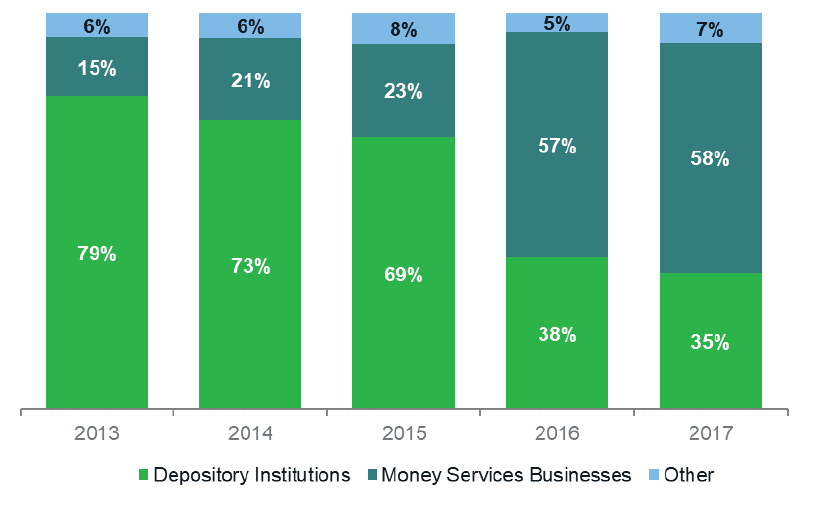

Filers reported a total of $1.7 billion in suspicious activities in 2017 .......... 14

Nearly 80 percent of EFE SARs involved a monetary loss ........................ 15

Older adults’ monetary losses were more common and greater than filers’

losses ............................................................................................ 15

One third of the individuals who lost money were ages 80 and older ......... 16

Adults ages 70 to 79 had the highest average monetary loss .................... 17

Monetary losses were greater when the older adult knew the suspect ....... 17

5. Patterns in EFE SARs ...................................................................................... 19

Types of suspicious activity varied significantly by filer ............................. 19

More than half of EFE SARs involved a money transfer ............................ 21

Checking or savings accounts had the highest monetary losses ................ 22

The suspicious activity reported in a SAR took place, on average, over a

four-month period ........................................................................... 22

Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs indicated that the filer reported the

suspicious activity to a local, state or federal authority ..................... 23

6. Implications and Next Steps .......................................................................... 25

2 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX A: METHODOLOGY ....................................................................... 28

APPENDIX B: DETAILED TABLES ................................................................. 31

APPENDIX C: BUREAU INITIATIVES TO HELP FINANCIAL

INSTITUTIONS FIGHT ELDER FINANCIAL EXPLOITATION .............. 34

APPENDIX D: GLOSSARY ................................................................................ 35

3 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Executive Summary

Since 2013, financial institutions have reported to the federal government over 180,000

suspicious activities targeting older adults, involving a total of more than $6 billion. These

reports indicate that financial exploitation of older adults by scammers, family members,

caregivers, and others is widespread in the United States. The reports also provide unique data

on these suspicious activities, which can enhance ongoing efforts to prevent elder financial

exploitation and to punish wrongdoers.

This study analyzes a rich, non-public data set to shed light on the volume and characteristics of

elder financial exploitation (EFE). The study explores the Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs)

filed with the federal government by financial institutions such as banks and money services

businesses. This is the first public analysis of EFE SAR filings since the Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which receives and maintains the database of SARs,

introduced electronic SAR filing with a designated category for “elder financial exploitation” in

2013.

This report presents findings based on selected data fields from all EFE SARs filed between 2013

and 2017. The report also presents findings based on a representative sample of SAR transcripts,

which include a narrative portion supplied by the financial institution. The findings provide an

opportunity to better understand the complex problem of elder financial exploitation and to

identify ways to improve prevention and response.

Key findings

• SAR filings on elder financial exploitation quadrupled from 2013 to 2017. In

2017, elder financial exploitation (EFE) SARs totaled 63,500. Based on recent prevalence

studies, these 2017 SARs likely represent a tiny fraction of actual incidents of elder

financial exploitation.

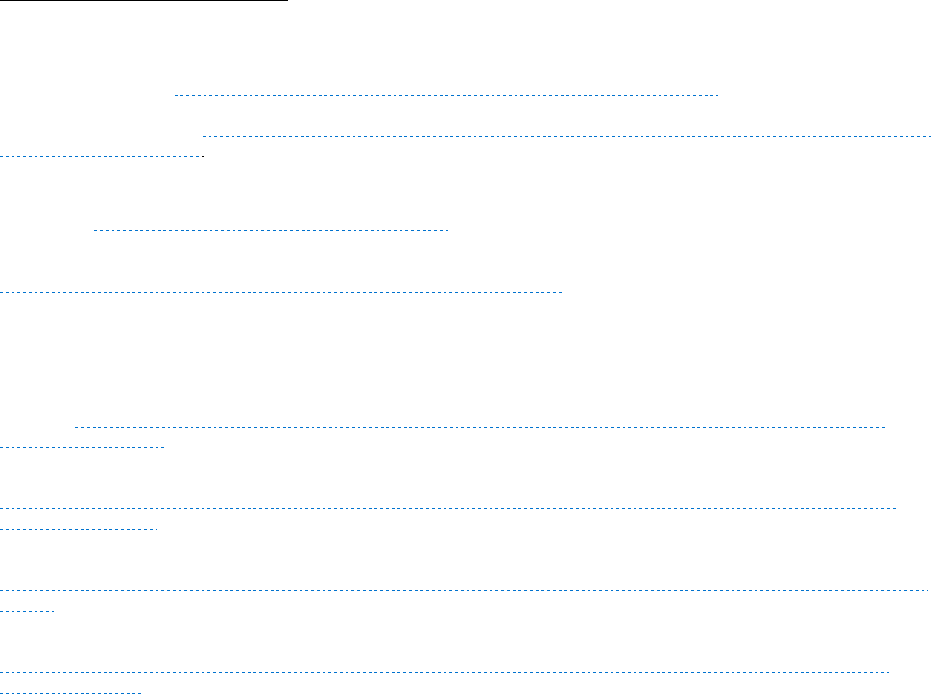

• Money services businesses have filed an increasing share of EFE SARs. In

2016, money services business (MSB) filings surpassed depository institution (DI)

filings. In 2017, MSB SARs comprised 58 percent of EFE SARs, compared to 15 percent

in 2013.

• Financial institutions reported a total of $1.7 billion in suspicious activities

in 2017, including actual losses and attempts to steal the older adults’ funds.

4 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

• Nearly 80 percent of EFE SARs involved a monetary loss to older adults

and/or filers (i.e. financial institutions).

• In EFE SARs involving a loss to an older adult, the average amount lost was

$34,200. In 7 percent of these EFE SARs, the loss exceeded $100,000.

• When a filer lost money, the average loss per filer was $16,700.

• One third of the individuals who lost money were ages 80 and older.

• Adults ages 70 to 79 had the highest average monetary loss ($45,300).

• Losses were greater when the older adult knew the suspect. The average loss

per person was about $50,000 when the older adult knew the suspect and $17,000 when

the suspect was a stranger.

• Types of suspicious activity varied significantly by filer. When the filer was an

MSB, 69 percent of EFE SARs described scams by strangers. DI filings, in contrast,

involved an array of financial crimes, with 27 percent involving stranger scams.

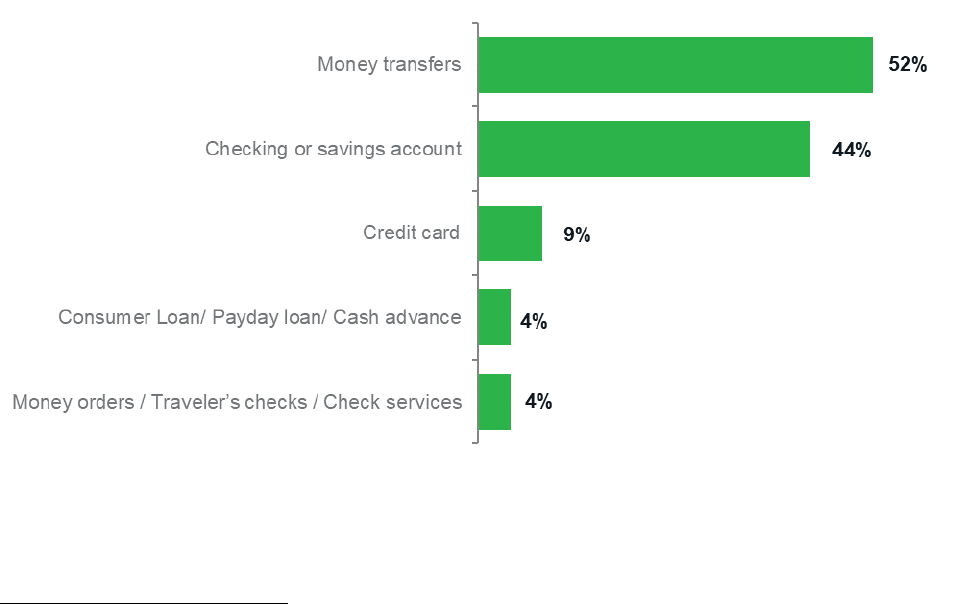

• More than half of EFE SARs involved a money transfer. The second-most

common financial product used to move funds was a checking or savings account (44

percent).

• Checking or savings accounts had the highest monetary losses. The average

monetary loss to the older adult was $48,300 for EFE SARs involving a checking or

savings account while the average loss was $32,800 for EFE SARs involving a money

transfer.

• The suspicious activity reported in an EFE SAR took place, on average, over

a four-month period.

• Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs indicated that the filer reported the

suspicious activity to a local, state, or federal authority. Only one percent of

MSB SARs stated that the MSB reported the suspicious activity in the SAR to a

government entity such as adult protective services or law enforcement.

Implications for key stakeholders

• SARs indicate that elder financial exploitation is widespread and damaging.

This analysis of EFE SARs highlights the need for strong and diverse interventions by

financial institutions, law enforcement, and social services, as well as the involvement of

policymakers.

5 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

• Financial institutions are filing an increasing number of EFE SARs, but in

most cases the SARs do not indicate that financial institutions are reporting

elder financial exploitation to law enforcement or adult protective services.

This is a missed opportunity to increase investigation and prosecution, and to make it

more likely that victims will receive appropriate services.

• EFE SARs are a useful and untapped resource for monitoring and

measuring elder financial exploitation. Regularly studying the trends, patterns

and issues in EFE SARs can help stakeholders enhance protections through independent

and collaborative work.

• The types of suspects and activities reported by money services businesses

and depository institutions differ significantly, and interventions can be

tailored accordingly. Key stakeholders and policymakers can read the findings and

develop new responses. This report suggests distinct strategies that MSBs and DIs can

implement.

• Law enforcement can mine the growing database of EFE SARs to be more

proactive in investigating cases and bringing more prosecutions. This use of

SARs by law enforcement can trigger new investigations, enhance ongoing inquiries, and

increase prosecutions.

6 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

1. Introduction

Since 2013, financial institutions have reported to the federal government over 180,000

suspicious activities targeting older adults, involving more than $6 billion. These reports

indicate that financial exploitation of older adults by scammers, family members, caregivers,

and others is widespread in the United States. The reports also provide unique data on these

suspicious activities, which can enhance ongoing efforts to prevent elder financial exploitation

and to punish wrongdoers.

This study analyzes a rich, non-public data set to shed light on the volume and characteristics of

elder financial exploitation (EFE). The study explores the Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs)

filed with the federal government by financial institutions such as banks and money services

businesses. This is the first public analysis of EFE SAR filings since the Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which receives and maintains the database of SARs,

introduced electronic SAR filing with a designated category for “elder financial exploitation” in

2013.

1

The analysis shows that the EFE SAR monthly filings quadrupled from 2013 to 2017, with

money services businesses (MSBs) filing an increasing share of these SARs. EFE SARs likely

account for a tiny fraction of actual incidents of elder financial exploitation.

The amount of money that fraudsters and exploiters stole or attempted to steal from older adults

is substantial. In 2017, filers reported that $1.7 billion was involved in suspected incidents.

When a monetary loss occurred, older adults lost on average $34,200.

While financial institutions are increasingly filing EFE SARs, they often do not indicate that they

reported the suspicious activity to first responders. Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs specify

that filers reported the activity to adult protective services, law enforcement, or other

authorities.

1

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Office of Financial Protection for Older Americans is the author of this

report. The Bureau’s Office of Research contributed to the analysis of the SARs data and preparation of the report.

The Office would also like to recognize the support of the U.S. Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network.

7 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

This report presents findings based on selected data fields from all EFE SARs filed between 2013

and 2017. The report also presents findings based on a representative sample of SAR transcripts,

which include a narrative portion supplied by the financial institution.

2

The findings provide an

opportunity to better understand the complex problem of elder financial exploitation and to

identify ways to improve prevention and response.

2

See Appendix A for detailed information about the data and methodology.

8 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2. Background

Elder financial exploitation is the illegal or improper use of an older person’s funds, property or

assets.

3

Perpetrators include a wide variety of people ranging from close family members to

offshore scammers.

4

Studies show that financial exploitation is the most common form of elder

abuse and yet only a small fraction of incidents are reported.

5

Estimates of annual losses to older

adults have ranged from $2.9 billion to $36.5 billion.

6

Financial institutions are uniquely positioned to prevent and respond to elder financial

exploitation. They often come in contact with victims and/or perpetrators. Many financial

institutions know their customers personally. In addition, financial institution personnel

frequently have the opportunity to observe how funds move from the older person to the

perpetrator. For example, a perpetrator may steal an older adult’s funds or investments from a

bank, credit union or brokerage account, or an older adult may transmit funds to a perpetrator

using a financial product.

Suspicious Activity Reports

Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) are one way that financial services providers report a

suspected financial crime to the government and, ultimately, to law enforcement. SARs help law

enforcement entities identify individuals involved in a broad spectrum of financial crimes,

3

HHS, Nat’l Ctr. on Elder Abuse, Admin. on Cmty. Living, Types of Abuse, Financial or Material Exploitation,

https://ncea.acl.gov/faq/abusetypes.html#financial

(last visited Feb. 27, 2019).

4

MetLife Mature Market Institute, The MetLife Study of Elder Financial Abuse: Crimes of Occasion, Desperation,

and Predation Against America’s Elders (June 2011), available at

https://www.giaging.org/documents/mmi-elder-

financial-abuse.pdf (Referred to as Metlife Study); True Link Financial, The True Link Report on Elder Financial

Abuse 2015 (Jan. 2015), available at https://truelink-wordpress-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-

content/uploads/True-Link-Report-On-Elder-Financial-Abuse-012815.pdf (Referred to as TrueLink Study).

5

Ron Acierno, et al., Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual, and Financial Abuse and Potential

Neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study, 100 Am. J. Pub. Health 292-97 (Feb. 2010),

available at http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089; Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., et al., Under the Radar:

New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study–Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys–Final

Report, 50 (May 2011), available at

https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf (estimating

that only 1 in 44 cases of financial abuse came to the attention of agencies that provide services to victims of elder

abuse in New York State).

6

See Metlife Study and TrueLink Study, supra note 4. Estimates vary significantly, largely due to definitional and

methodological differences. For a discussion of the MetLife and True Link methodologies, see Tobie Stanger,

Financial Elder Abuse Costs $3 Billion a Year. Or is it $36 billion?, Consumer Reports (Sept. 29, 2015), available at

https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/consumer-protection/financial-elder-abuse-costs--3-billion-----or-is-it--

30-billion- (last visited Feb. 27, 2019). Both studies extrapolated from sample data to reach estimates of losses for the

entire older population of the United States.

9 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

including elder financial exploitation. Law enforcement entities can use SARs to fight crime, as

they may use the information in SARs to trigger investigations, support ongoing investigations,

and identify subjects. Access to SARs and their use is restricted under federal law. Knowledge

concerning the existence of a SAR is strictly confidential and is generally limited to law

enforcement and financial regulatory authorities.

7

Information in SARs forms the basis for identifying emerging trends and patterns associated

with financial crimes. Those trends, in turn, help law enforcement agencies and provide

feedback to financial institutions.

8

The federal Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) mandates that financial institutions report suspicious

activity that might indicate money laundering, tax evasion, or other criminal activities to the

federal government.

9

Financial institutions file SARs with the U.S. Department of the

Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). The types of financial institutions

that must file SARs include banks,

10

casinos,

11

money services businesses,

12

brokers or dealers,

13

insurance companies,

14

mutual funds,

15

futures commissions merchants and introducing

brokers in commodities,

16

loan or finance companies,

17

and housing government-sponsored

enterprises.

18

These financial institutions must file SARs with FinCEN if certain dollar

7

Treas., FinCEN & CFPB, Memorandum on Financial Institution and Law Enforcement Efforts to Combat Elder

Financial Exploitation (Aug. 2017), available at

https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201708_cfpb-treasury-fincen_memo_elder-

financial-exploitation.pdf (Referred to as Joint Memorandum).

8

FinCEN, Guidance on Preparing a Complete & Sufficient Suspicious Activity Report Narrative (Nov. 2003),

available at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/sarnarrcompletguidfinal_112003.pdf

.

9

31 U.S.C. § 5311 et seq.

10

31 C.F.R. § 1020.320. “Bank” includes a credit union, private bank, and trust company. 31 C.F.R. § 1020.100.

11

31 C.F.R. § 1021.320.

12

31 C.F.R. § 1022.320. A money services business includes any person doing business as: a currency dealer or

exchanger; a check casher; an issuer of traveler’s checks, money orders or stored value; a money transmitter; and the

U.S. Postal Service. For most of these types of businesses, there are additional criteria for whether specific entities are

included in the definition of a money services business. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.100(ff).

13

31 C.F.R. § 1023.320.

14

31 C.F.R. § 1025.320.

15

31 C.F.R. §1024.320.

16

31 C.F.R. § 1026.320.

17

31 C.F.R. § 1029.320.

18

31 C.F.R. § 1030.320.

10 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

thresholds are met and the financial institution knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect a

transaction conducted or attempted by, at, or through the financial institution:

• involves funds derived from illegal activity or attempts to disguise funds derived from

illegal activity,

• is designed to evade Bank Secrecy Act regulations,

• lacks a business or apparent lawful purpose, or

• involves the use of the financial institution to facilitate criminal activity.

19

SAR filing is mandatory when a suspicious transaction involves or aggregates to at least $5,000

in funds or assets ($2,000 for money services businesses).

20

Financial institutions may also file

SARs voluntarily if the transaction is below the regulatory dollar threshold.

In February 2011, FinCEN issued an Advisory noting that SARs are a valuable avenue for

financial institutions to report elder financial exploitation.

21

FinCEN did not define the term

“elder financial exploitation” for filers or specify the minimum age at which a person is

considered a victim of elder financial exploitation. The Advisory includes several red flags that

may signal elder financial abuse. It also provides instructions on SAR filing when a financial

institution detects activity that appears suspicious. In April 2013, FinCEN introduced electronic

SAR filing with a designated category for “elder financial exploitation.” FinCEN instructs filers

to include a “clear, complete, and concise” description of the suspicious activity in the SAR

narrative field.

22

19

Joint Memorandum, supra note 8; 31 C.F.R. §§ 1020.320, 1021.320, 1022.320, 1023.320, 1024.320, 1025.320,

1026.320, 1029.320, 1030.320.

20

31 C.F.R. §§ 1020.320, 1021.320, 1022.320, 1023.320, 1024.320, 1025.320, 1026.320, 1029.320, 1030.320. In

addition, a bank must file a SAR for insider abuse involving any amount, violations aggregating to $5,000 or more

where a suspect can be identified, and violations aggregating to $25,000 or more regardless of whether the bank can

identify a suspect. 12 CFR §§ 21.11(c)(3), 163.180(d)(3)(iii), 208.62(c)(3), 353.3(a)(3), 748.1(c)(1)(iii).

21

FinCEN, FIN-2011-A003, Advisory to Financial Institutions on Filing Suspicious Activity Reports on Elder

Financial Exploitation (Feb. 22, 2011), available at

https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/advisory/fin-2011-

a003.pdf (Referred to as FIN-2011-A003, Advisory to Financial Institutions).

22

FinCEN, FinCEN Suspicious Activity Report (FinCEN SAR) Electronic Filing Instructions (Oct. 2012), available at

https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FinCEN%20SAR%20ElectronicFilingInstructions-%20Stand%20

Alone%20doc.pdf.

11 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

3. Trends in SAR submissions

SAR filings on elder financial exploitation

quadrupled from 2013 to 2017

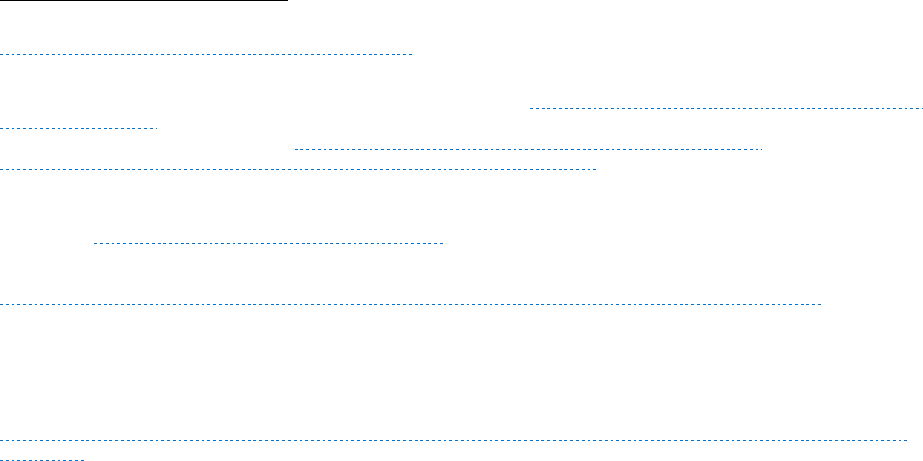

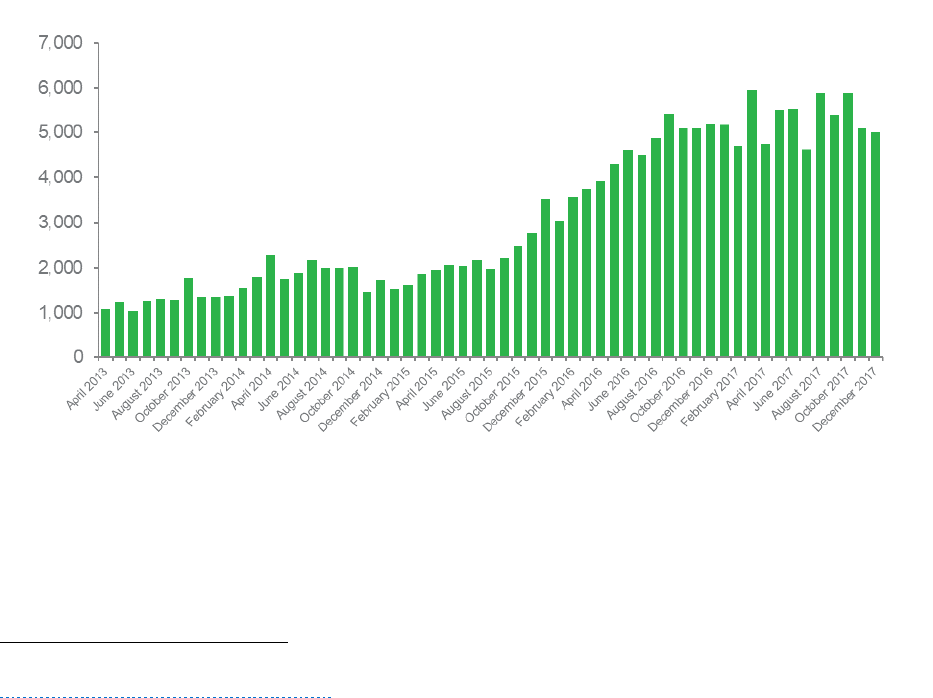

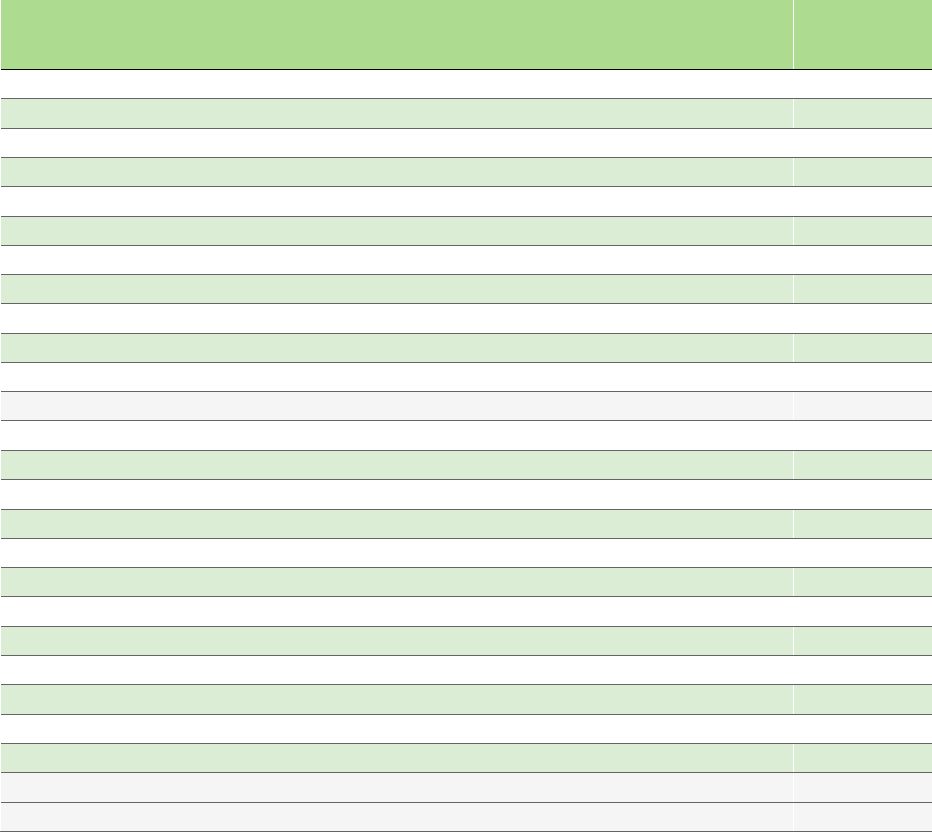

SARs on elder financial exploitation (EFE SARs) have increased from an average of about 1,300

filed per month in 2013 to about 5,300 filed per month in 2017. This is more than a fourfold

increase. In contrast, SARs on all types of suspicious activities have increased from an average of

about 121,200 per month in 2013 to about 161,100 per month in 2017, a 40 percent increase.

23

The rapidly increasing number of EFE SAR submissions may be due to a number of factors,

including the growing number of older adults, a possible increase in the incidence of elder

financial exploitation, growing awareness of FinCEN’s 2011 Advisory, and the addition of elder

financial exploitation as a category on the SAR form.

FIGURE 1: NUMBER OF EFE SARs BY MONTH (APRIL 2013-DECEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of EFE SARs filed between April 2013 and December 2017 (176,690 SARs)

23

The number of all SARs submitted between April 2013 and December 2017 was obtained from FinCEN SARStats

https://www.fincen.gov/reports/sar-stats

(last visited Feb. 27, 2019).

12 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

In total, filers (i.e. financial institutions) submitted approximately 176,700 EFE SARs between

April 2013 and December 2017. In 2017, EFE SARs filings totaled 63,500.

Despite the high number of EFE SARs in 2017, these 63,500 SARs may account for less than 2

percent of actual incidents in 2017, according to estimated prevalence rates of elder financial

exploitation.

24

Applying one of the lowest prevalence rates, 5.2 percent, to the U.S. Census’

estimated population of 71 million adults age 60 and older in 2017 results in the estimate that

more than 3.5 million older adults were victims of elder financial exploitation that year.

25

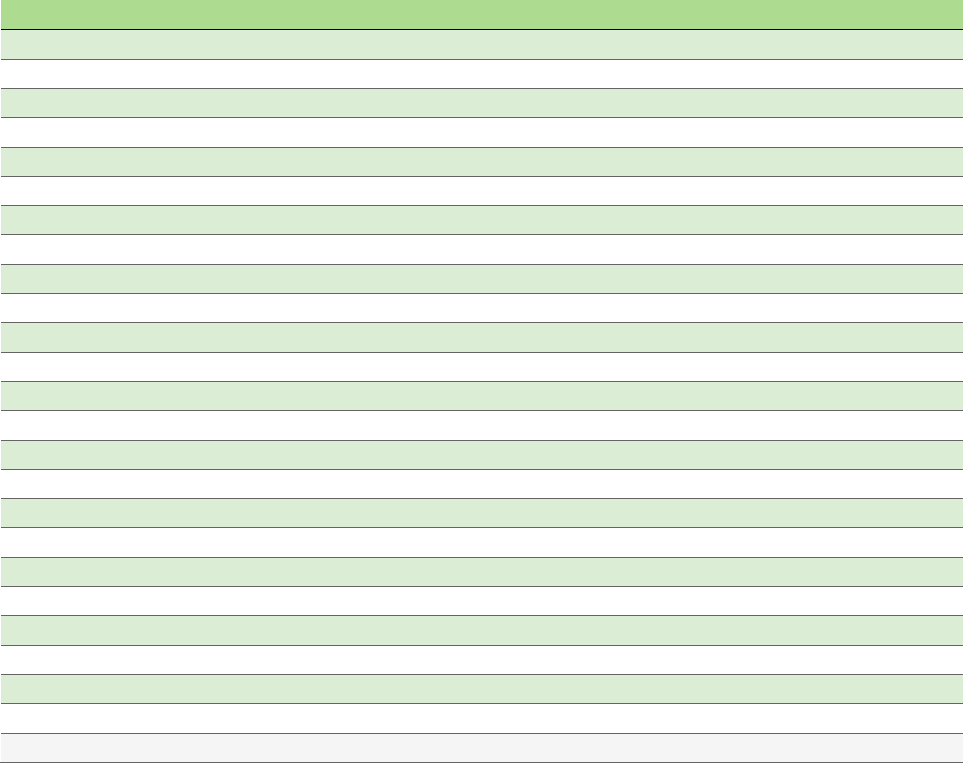

Money services businesses have filed an

increasing share of EFE SARs

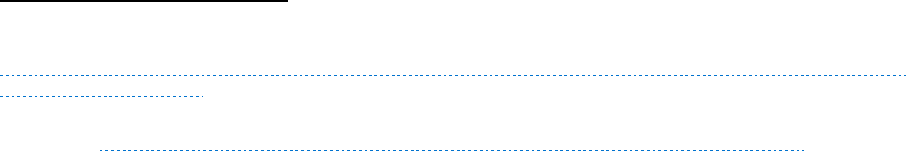

Depository institutions (DI) submitted over 70 percent of all SARs on elder financial

exploitation from 2013 through 2015. In 2016, this trend shifted significantly when money

services business (MSB) filings surpassed DI filings.

26

Filings by other entities have remained a

relatively constant share of EFE SARs since 2013.

24

Estimated prevalence rates of elder financial exploitation from studies range from as low as 3.5 percent to as high

as 15 percent, depending on the age group, time period and definition of elder abuse adopted. HHS, Nat’l Ctr. on

Elder Abuse, Admin. on Cmty. Living, What is Known about the Incidence and Prevalence of Elder Abuse in the

Community Setting?, https://ncea.acl.gov/whatwedo/research/statistics.html#prevalence

(last visited Feb. 27,

2019); Michaela Beals & Martha Deevy, The scope of the problem: An overview of fraud prevalence measurement

(Nov. 2013), available at

http://longevity.stanford.edu/2013/11/14/the-scope-of-the-problem-an-overview-of-fraud-

prevalence-measurement.

25

Ron Acierno, et al., Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual and Financial Abuse and Potential

Neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study, 100 Am. J. Pub. Health 292-97 (Feb. 2010),

available at http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089

(showing the prevalence rate of elder financial exploitation

by a caregiver or family member); U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey Table S0102 Population 60

years and over in the United States 1-Year Estimates,

https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/S0102 (last visited Feb. 27, 2019).

26

In recent years, federal law enforcement agencies have brought several civil and criminal actions against large

money services businesses for, among other things, failing to meet their anti-money laundering (AML) obligations

under the Bank Secrecy Act and, specifically, failing to implement procedures to file required SARs when victims

reported fraud on transactions over $2,000. See F.T.C., MoneyGram Agrees to Pay $125 Million to Settle Allegations

that the Company Violated the FTC’s 2009 Order and Breached a 2012 DOJ Deferred Prosecution Agreement (Nov.

8, 2018),

https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2018/11/moneygram-agrees-pay-125-million-settle-

allegations-company (2018 agreement between MoneyGram International, Inc. and the Federal Trade Commission);

U.S. Dep’t. of Justice, Western Union Admits Anti-Money Laundering and Consumer Fraud Violations, Forfeits

$586 Million in Settlement with Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission (Jan. 19, 2017),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/western-union-admits-anti-money-laundering-and-consumer-fraud-violations-

forfeits-586-million (2017 agreement between the Western Union Company, the Department of Justice, the Federal

Trade Commission and several U.S. Attorneys’ Offices); FinCEN, FinCEN Fines Western Union Financial Services,

Inc. for Past Violations of Anti-Money Laundering Rules In Coordinated Action with DOJ and FTC (Jan. 19, 2017),

https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-fines-western-union-financial-services-inc-past-violations-anti-

money (related 2017 FinCEN penalty against Western Union for AML program failures and violations of its SAR filing

obligations); U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Moneygram International Inc. Admits Anti-Money Laundering and Wire Fraud

Violations, Forfeits $100 Million in Deferred Prosecution (Nov. 9, 2012),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/moneygram-international-inc-admits-anti-money-laundering-and-wire-fraud-

violations-forfeits (2012 agreement between MoneyGram International Inc. and the Department of Justice).

13 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

FIGURE 2: PERCENT OF EFE SARs FILED BY FILER TYPE (APRIL 2013 – DECEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of EFE SARs filed between April 2013 and December 2017 (176,690 SARs)

Note: “Other” filers category includes casinos, brokers or dealers, insurance companies, mutual funds, futures commissions

merchants and introducing brokers in commodities, loan or finance companies, and housing government-sponsored

enterprises.

14 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

4. Monetary losses reported in

EFE SARs

Filers reported a total of $1.7 billion in

suspicious activities in 2017

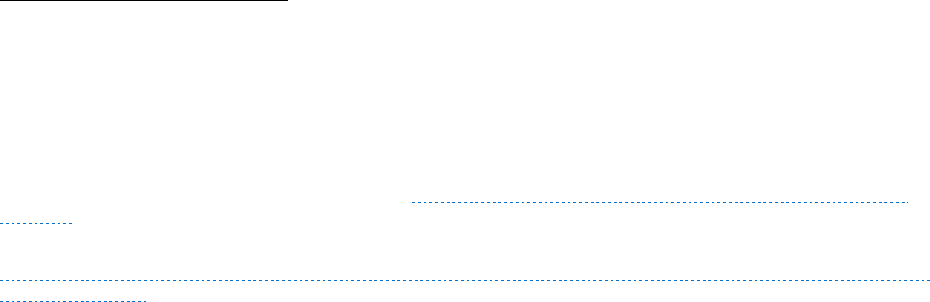

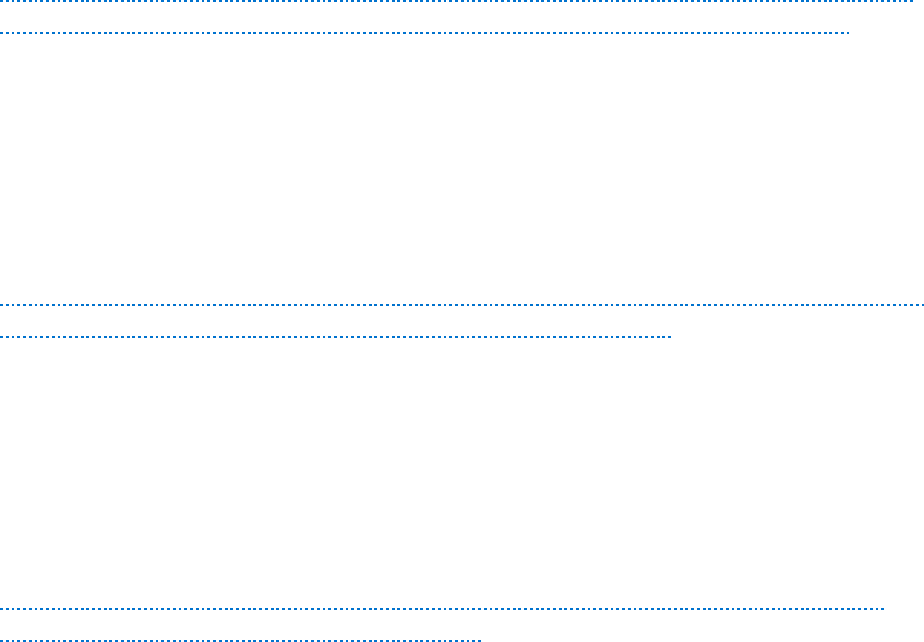

The dollar amounts listed in suspicious activities reported in EFE SARs include actual losses to

the older adult or to the filer, attempts to steal the older adults’ funds, or both. Financial

institutions reported $6 billion in actual losses and attempts in EFE SARs filed between April

2013 and December 2017.

27

In 2014, actual losses and attempts totaled $931 million. In 2017,

actual losses and attempts totaled $1.7 billion.

FIGURE 3: TOTAL AMOUNT OF MONETARY LOSSES AND ATTEMPTS REPORTED IN EFE SARs BY YEAR

(IN BILLIONS)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of all EFE SARs filed between April 2013 and December 2017 (183,360 SARs).

Note: Analysis includes dollar amounts reported in EFE SARs with continuing activities, but excludes EFE SARs in the

highest 1% by dollar amount per year. *Total dollar amounts for 2013 are limited to April to December.

27

The analysis excludes the top 1 percent of SARs by dollar amount involved per year. The top 1 percent of SARs

account for a total of $142.1 billion or 96 percent of all dollar amounts involved in suspicious activities for the 2013-

2017 time period. Many SARs in the top 1 percent of SARs by dollar amount, for instance, describe scams involving an

attempt to deposit a fake check purportedly worth millions of dollars or attempts to withdraw billions of dollars from

a customer’s account. These monetary amounts in suspicious activities are uncommon, rarely involve actual losses,

and result in wide variations in the total dollar amount over time. Appendix A provides more details about this

exclusion.

15 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

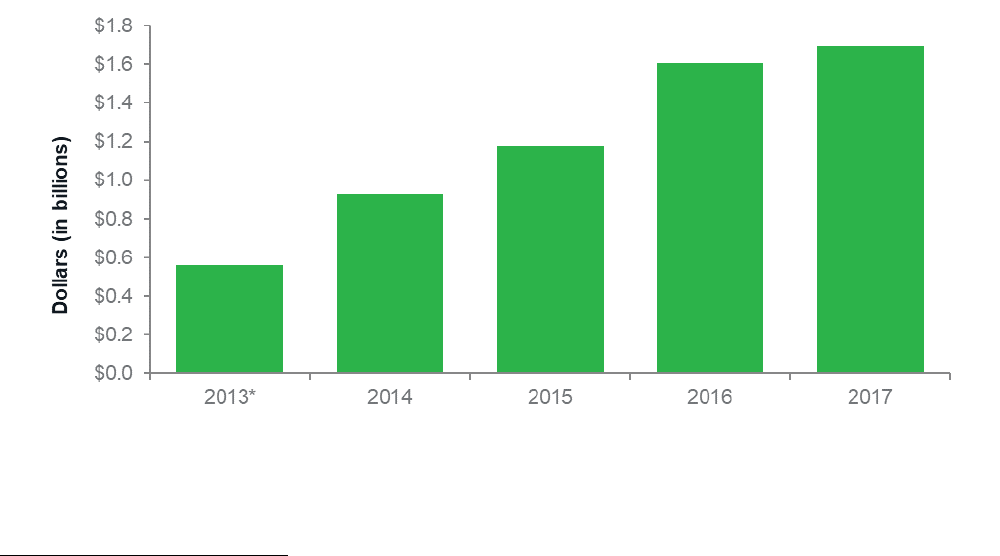

Nearly 80 percent of EFE SARs involved a

monetary loss

Nearly 80 percent of EFE SARs involved a monetary loss to older adults and/or the filer. In

about half of EFE SARs, the entire amount reported was a monetary loss to older adults, the

filer, or both. In 28 percent of EFE SARs, the amount reported included both a monetary loss

and an attempted theft of the older adult’s funds.

28

Only 15 percent of EFE SARs describe solely

an attempt with no actual monetary losses involved. These SARs often describe transactions that

were blocked, rescinded, or refunded with no loss to the customer or filer.

FIGURE 4: PERCENT OF EFE SARs WITH A MONETARY LOSS AND/OR ATTEMPT (APRIL 2013 –

SEPTEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Older adults’ monetary losses were more

common and greater than filers’ losses

In about 75 percent of EFE SARs, the targeted older adult lost money. In contrast, the filer (i.e.

the financial institution) lost money in 9 percent of all EFE SARs. Monetary losses are greater

for older adults than filers. The average amount lost per older adult was $34,200.

29

In 7 percent

28

We also use the term “partial loss” to describe the cases involving losses and attempts.

29

Average and median loss amounts reported are per older adult. Fewer than 10 percent of EFE SARs had more than

one targeted individual identified. Appendix A provides more details about this analysis.

16 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

of these SARs, the loss to the older adult exceeded $100,000.

30

In contrast, the average amount

lost per filer was $16,700, and there were no cases involving losses of more than $100,000 by

the filer.

31

FIGURE 5: PERCENT OF EFE SARs WITH A LOSS TO OLDER ADULTS OR FILERS AND AVERAGE LOSS

(APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Target

Percent of EFE SARs

involving a loss

a

Average (median)

loss

Older adult 75% $34,200 (13,900)

b

Filer 9% $16,700 (14,600)

c

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Notes: (a) Percentages include EFE SARs with partial losses. (b) Average and median loss amounts are per targeted older

adult. These amounts are based on the 44 percent of EFE SARs where the entire amount reported is a monetary loss to the

older adult. Excludes SARs with no losses or partial losses to the older adult or any losses to the filer. (c) Average and

median loss amounts for filers are based on the 2 percent of EFE SARs where the entire amount reported is a monetary

loss to the filer. Excludes SARs with no losses or partial losses to the filer or any losses to older adults.

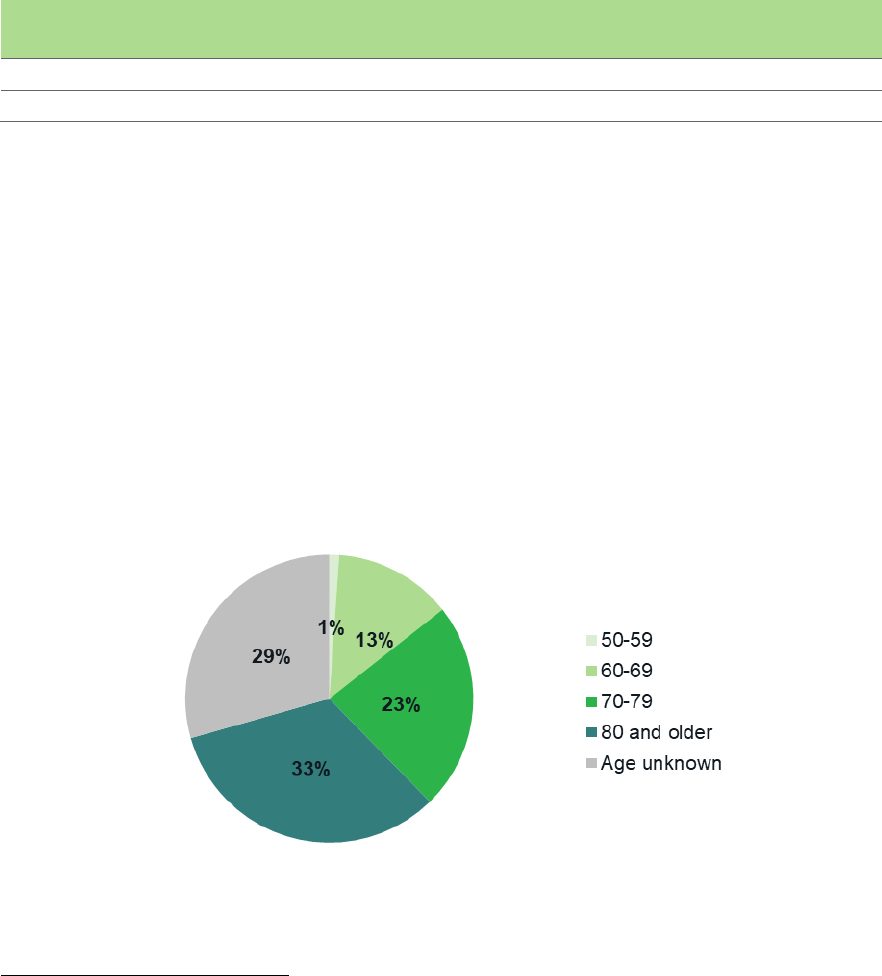

One third of the individuals who lost money

were ages 80 and older

One third of targeted individuals who lost money were adults ages 80 and older. Given that

nearly 30 percent of EFE SARs involving a loss to the older adult do not specify the age of the

targeted older adult, it is likely that adults 80 and older may account for more than 40 percent.

32

FIGURE 6: PERCENT OF EFE SARs WITH A LOSS TO OLDER ADULTS BY AGE GROUP (APRIL 2013 –

SEPTEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (459 SARs)

30

Based on the EFE SARs where the entire amount reported was a monetary loss to the older adult.

31

Based on the EFE SARs where the entire amount reported was a monetary loss to the filer.

32

FinCEN has not specified a minimum age for designating that the suspicious activity reported in a SAR constitutes

elder financial exploitation. As a result, some EFE SARs identified individuals as young as age 50 as targets of EFE.

17 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Note: Excludes EFE SARs with no losses or partial losses to the older adult or any losses to the filer. Percentages do not

add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

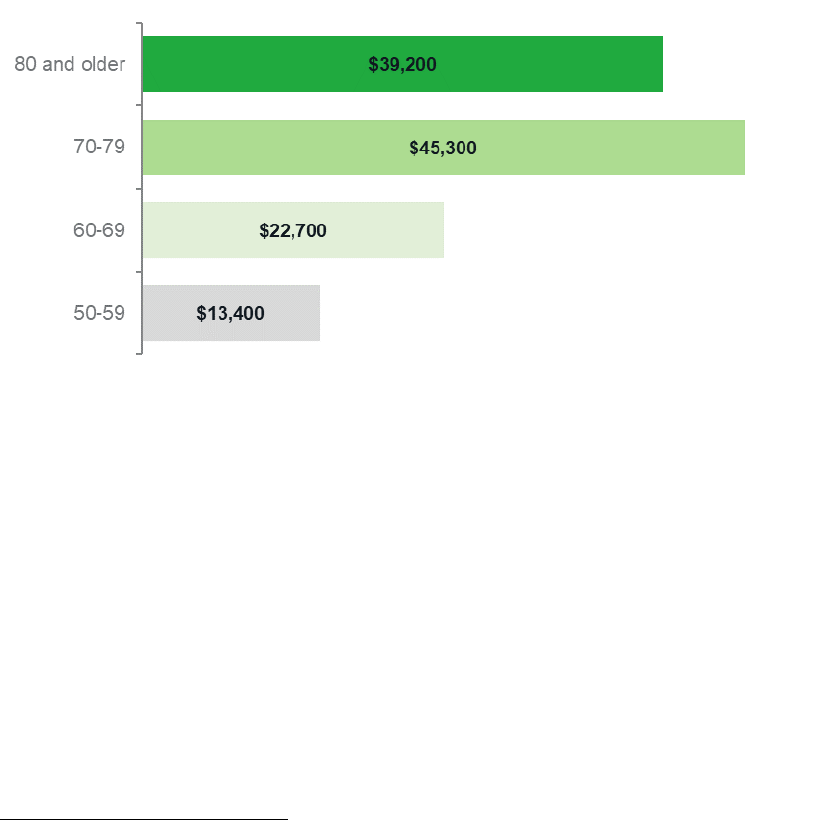

Adults ages 70 to 79 had the highest average

monetary loss

EFE SARs involving adults ages 70 to 79 had the highest average monetary loss ($45,300). EFE

SARs involving adults ages 80 and older had the second highest average monetary loss

($39,200). The average monetary loss of $41,800 for the two oldest age categories combined

(ages 70-79 and 80 and older) is approximately $20,000 higher than the average monetary loss

of $22,000 for the two youngest age categories combined (ages 50-59 and 60-69).

FIGURE 7: AVERAGE MONETARY LOSS BY AGE OF THE TARGETED OLDER ADULT (APRIL 2013 –

SEPTEMBER 2017)

a

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (324 SARs)

Note: Based on EFE SARs where the age of the targeted adult(s) is stated. Excludes EFE SARs showing no loss or a partial

loss to the older adult or any loss to the filer.

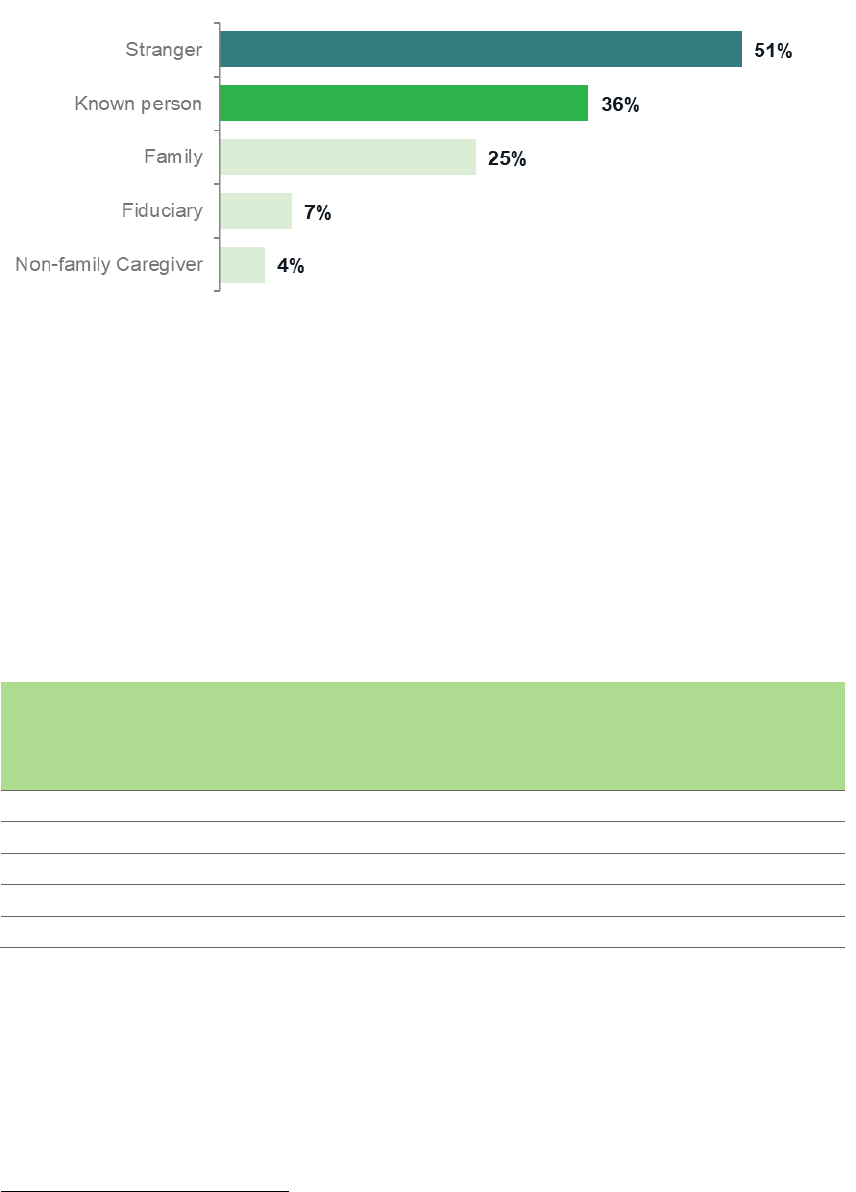

Monetary losses were greater when the older

adult knew the suspect

EFE SARs identify a variety of suspects. These suspects included strangers as well as people

known to the older adult(s).

33

33

Approximately 14 percent of all SARs do not provide enough information to determine the relationship of the

suspect to the targeted older adult.

18 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

FIGURE 8: PERCENT OF EFE SARs BY SUSPECT CATEGORY

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Notes: (a) Percentages add up to more than 100 percent because EFE SARs may indicate multiple types of suspects. (b)

The known person category includes fiduciaries, family members, non-family caregivers and others individuals such as

friends, neighbors, accountants, and contractors. (c) The fiduciary category includes family members and non-family

caregivers who serve as fiduciaries. (d) The family member and non-family caregiver categories include fiduciaries.

A monetary loss was more common, and the amount lost was greater, when the older adult knew

the suspect than when suspects were strangers. In addition, a loss was more common, and the

amount lost was greater, when the suspects were fiduciaries.

34

About 7 percent of all EFE SARs

involved a suspect identified as a fiduciary, such as an agent under a power of attorney.

FIGURE 9: PERCENT OF EFE SARs WITH A LOSS TO THE OLDER ADULT AND AVERAGE MONETARY

LOSS BY SUSPECT CATEGORY (APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Suspect

Category

Percent of EFE SARs

within a suspect

category involving

a loss to the older adult

a

Average (median)

loss per older adult

b

Stranger

75%

$17,000 ($8,500)

Known person

c

79% $50,200 ($23,200)

Family

d

82% $42,700 ($24,900)

Fiduciary

e

88% $83,600 ($33,800)

Non-family caregiver

e

76%

$57,800 ($21,800)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Notes: (a) Percentages include EFE SARs with partial losses. (b) Average and median loss amounts per older adult are

based on the EFE SARs where the entire amount reported is a monetary loss to the older adult, and excludes SARs with no

losses, partial losses or any loss to the filer. (c) The known person category includes fiduciaries, family members, non-family

caregivers and others individuals such as friends, neighbors, accountants, and contractors. (d) The fiduciary category

includes family members and non-family caregivers who serve as fiduciaries. (e) The family member and non-family

caregiver categories include fiduciaries.

34

A fiduciary is a person with authority to manage money or property for someone else. Fiduciaries have a legal duty

to manage a person’s money and property for the person’s benefit. Types of fiduciaries include agents under a power

of attorney, guardians of property, trustees, and government benefit fiduciaries.

19 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

5. Patterns in EFE SARs

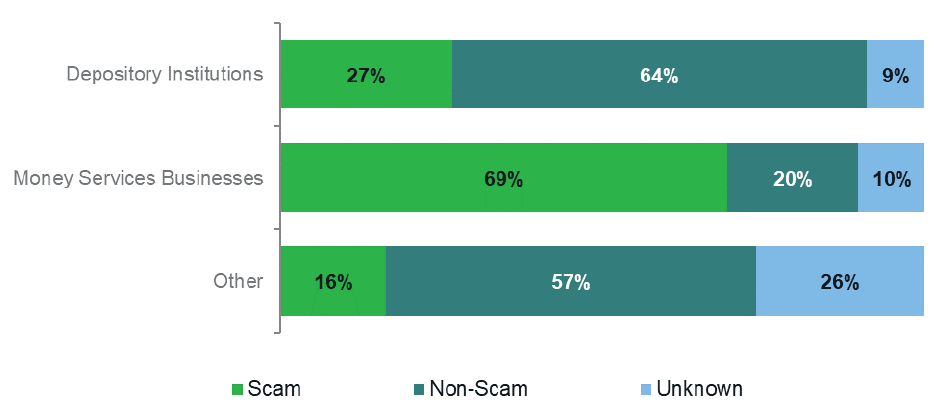

Types of suspicious activity varied significantly

by filer

Elder financial exploitation SARs describe a variety of types of financial exploitation. For this

analysis, the Bureau categorized the activities described in SARs as scams and non-scams. EFE

SARs related to scams are those where the filer specifically referred to the activity as a scam or

where the filer described a scheme involving the transfer of money to a stranger for a promised

benefit that the older adult did not receive. EFE SARs not categorized as scams include a broad

array of activities, including theft by family members or others known to the older adult,

account takeovers, identity theft, and other crimes. The prevalence of these activities varied

significantly by filer type (Figure 10). Figure 11, below, provides examples of four common

activity patterns described in EFE SARs.

FIGURE 10: TYPES OF ELDER FINANCIAL EXPLOITATION ACTIVITY DESCRIBED IN SARs BY FILER TYPE

(APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Note: “Other” filers category includes casinos, brokers or dealers, insurance companies, mutual funds, futures commissions

merchants and introducing brokers in commodities, loan or finance companies, and housing government-sponsored

enterprises.

20 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

FIGURE 11: FOUR COMMON ELDER FINANCIAL EXPLOITATION ACTIVITY PATTERNS*

Romance scam

An MSB reports that an older man requests a large money transfer to send to an

individual outside of the United States. The agent notes that the customer previously

sent small transfers abroad and asks the customer for more information about the

transaction. The customer explains that he is sending the money to his fiancée so she

can visit him. He met her online and this will be their first in-person meeting. The MSB

notes that the receiver has been the subject of previous SARs. The transaction is

blocked and the amount of the wire is refunded to the customer. The MSB does not

refund the fee. The MSB blocks future transactions by the customer.

Exploitation by

family

member/fiduciary

An older woman has a checking account at a bank. Her daughter contacts the bank

about the woman’s son. The son is the older woman’s agent under power of attorney.

The daughter claims that he is financially exploiting his mother. The bank finds that

there are a number of recent purchases and withdrawals using the customer’s debit

and ATM cards. Some transactions have occurred at liquor stores, casinos, and other

businesses that the customer has not patronized previously. In addition, a teller

informs the branch manager that the customer has visited the branch several times to

make cash withdrawals, accompanied by her son. The bank reports these incidents to

the local Adult Protective Services agency.

Theft by

caregiver

An older adult is a member of a large credit union. Credit union personnel notice an

unusual amount of activity in her account, including frequent large withdrawals at ATM

machines. In addition, an individual with a different last name has been cashing large

checks drawn on the account in person. The fraud department of the credit union calls

the member and she is unaware of the transactions. She states that the person

cashing the checks is one of her caregivers.

Money mule

A retired man received and sent numerous money transfers in a period of a few

months. He received the money transfers at several retail stores acting as agents for a

large MSB and sent the money transfers from outlets for the same MSB. The money

transfers he received originated in Europe as well as the United States. Shortly after

receiving these sums, he sent all or nearly all of the funds he received to individuals in

one African country. The MSB interviewed the man and asked him about the

transactions. He stated that he was sending funds to his nephew to help pay for food

and educational expenses. The MSB describes the pattern of transactions as “flipping.”

The MSB suspects that the man is the victim of a “person in need” scam.

*The activity patterns described above are illustrative of commonly seen elder financial exploitation patterns. They are

not based on individual or specific filings or SARs.

21 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Approximately 70 percent of MSB filings were related to scams. Romance, relative in need, and

lottery/sweepstake scams were the most common types of scams described in these filings. The

most common suspects in MSB filings were strangers. DI filings, in contrast, involved an array

of financial crimes. The activities described in these EFE SARs included theft, abuse of power of

attorney, and other fraudulent activity. While much less common than in MSB filings, 27

percent of DI filings involved scams. Two-thirds of suspects (66 percent) in DI filings were

people known to the older adult, while

few suspects in MSB SARs were people known to the

older adult.

More than half of EFE SARs involved a money

transfer

Funds move from the targeted person to the suspect using a variety of financial products and

services. In more than half of the EFE SARs analyzed, the targeted person used a money

transfer.

35

The second most common product was a checking or savings account (44 percent). A

credit card was the third most common product used. While most suspicious activities involved

a single type of product, two or more products were used in 19 percent of EFE SARs.

FIGURE 12: TOP 5 FINANCIAL PRODUCTS USED IN EFE SARs (APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Notes: Percentages add up to more than 100 percent because EFE SARs may indicate multiple types of products.

35

In a small number of SARs, the suspect conducts the money transfer. These SARs include cases of account

takeovers, where the suspect conducts a money transfer to other individuals or businesses using the older adults’

funds.

22 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Checking or savings accounts had the highest

monetary losses

The average monetary loss per older adult in EFE SARs that involved a checking or savings

account was $48,300. For SARs involving a money transfer, the average loss was $32,800, and

for a credit card, it was $32,600.

FIGURE 13: PERCENT OF EFE SARs WITH A LOSS TO THE OLDER ADULT AND AVERAGE MONETARY

LOSS BY PRODUCT (APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Product

Percent with

a loss to the older adult

a

Average (median)

loss per older adult

b

Checking or savings account

79%

$48,300 ($22,100)

Money transfer

78%

$32,800 ($9,900)

Credit card 63% $32,600 ($17,000)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (960 SARs)

Notes: (a) Percentages include SARs with partial losses. (b) Average and median loss amounts per older adult are based on

the EFE SARs where the entire amount reported is a monetary loss to the older adult. Excludes SARs with no losses or

partial losses to the older adult or any losses to the filer.

The suspicious activity reported in a SAR took

place, on average, over a four-month period

For each SAR, filers are required to provide the range of dates during which the suspicious

activity or activities occurred.

36

The average length of the suspicious activities in EFE SARs is

approximately four months (120 days).

37

In four specific situations, the suspicious activity in

EFE SARs lasts longer than the average length of time: when a joint account is involved (230

days); when a family member is the suspect (197 days); when the targeted person has

diminished capacity (158 days);

38

and when the targeted person is 80 years old and older (134

days). In nearly 30 percent of EFE SARs, activities span 10 days or fewer, and in 27 percent,

activities span 100 days or more.

36

Filers appear to use a variety of methods to assess the length of activity once a suspicious pattern becomes

apparent. In some SARs, they appear to use technology to look back at similar past transactions involving common

counterparties.

37

Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs).

38

In these SARs, the filer specifically mentioned that the targeted older adult had or appeared to have diminished

capacity or was under guardianship.

23 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

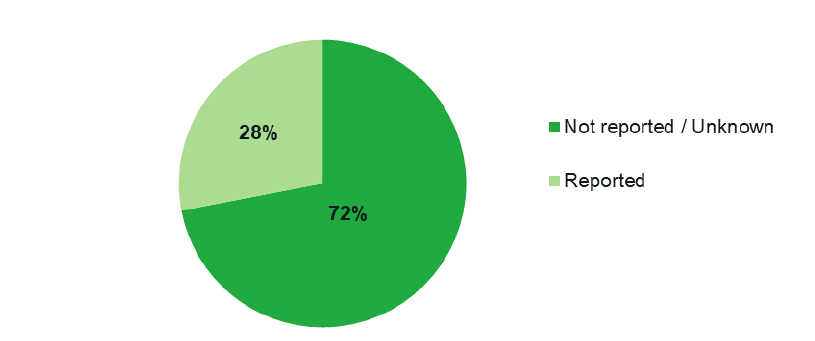

Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs indicated

that the filer reported the suspicious activity to a

local, state or federal authority

Research shows that only a small fraction of elder financial exploitation cases are reported to an

agency that can provide services to the older consumer.

39

Prompt reporting of suspected

financial exploitation to adult protective services, law enforcement, and other agencies can

trigger appropriate intervention, prevention of financial losses, and other remedies. SARs can

provide information to law enforcement and certain regulators about suspected elder financial

exploitation and references to supporting documentation that can trigger an investigation,

support an ongoing investigation, or identify previously unknown subjects and entities.

However, many law enforcement entities do not have direct access to FinCEN’s SAR database.

40

Moreover, law enforcement entities and financial regulatory authorities do not receive notice

when a financial institution files a SAR.

Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs (28 percent) indicate that the filer reported the suspicious

activity to a local, state or federal authority.

41

When filers did report suspicious activities to an

authority, they reported three times more often to adult protective services

42

(23 percent) than

to law enforcement (7 percent).

39

Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc. et al., Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study–Self-

Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys–Final Report, 50 (May 2011), available at

https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf.

40

Law enforcement entities that do not have a Memorandum of Understanding with FinCEN that allows such access

may be able to obtain SARs through their state or regional points of contact. See Joint Memorandum, supra note 8.

41

The SAR form contains a set of fields where filers can provide the contact information of any law enforcement

agency that the financial institution contacted. The narrative portion of the SAR may also include this type of

information.

42

Adult Protective Services (APS) are social services programs provided by states nationwide, serving older adults

and adults with disabilities who are in need of assistance. If APS finds that a person has experienced or is at risk of

experiencing financial exploitation, APS can decide what services, if any, are necessary for the vulnerable adult’s

safety or well-being and recommend a service plan. See Nat’l Center on Elder Abuse, What We Do,

https://ncea.acl.gov/whatwedo/practice/intervention-APS-howitworks.html

(last visited Feb. 27, 2019).

24 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

FIGURE 14: PERCENT OF EFE SARs NOTING A REPORT TO A LOCAL, STATE OR FEDERAL AUTHORITY

(APRIL 2013 – SEPTEMBER 2017)

Source: Bureau’s analysis of a random sample of EFE SARs (1,051 SARs)

Reporting of suspicious activities to a local, state, or federal authority varied significantly by filer

type. For example, slightly more than half of DI SARs indicate that the DI reported the

suspicious activity in the SAR to a government entity other than FinCEN, while only one percent

of MSB SARs indicate that the MSB reported the suspicious activity in the SAR.

25 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

6. Implications and Next Steps

The trends and patterns documented in this study provide new insight into the dimensions and

nature of financial exploitation of older adults and the responses of financial institutions when

they see it. Financial institutions, law enforcement, social service agencies, and policymakers at

the local, state, and federal level can use these detailed findings to strengthen efforts to prevent,

detect, and respond to this major threat to the financial security of older adults. The more than

fourfold increase in EFE SAR filings from 2013 to 2017 suggests that financial institutions are

taking the threat of financial exploitation more seriously and reporting it to FinCEN when they

see it.

SARs indicate that elder financial exploitation is widespread and damaging. In 2017

alone, financial institutions filed 63,500 EFE SARs. Filers reported $1.7 billion in suspicious

activities in 2017. The great majority of these amounts represent losses to older adults—and the

average individual loss to an adult over age 70 was $41,800. These reports likely represent just a

tiny fraction of this pervasive problem: elder financial exploitation SARs in 2017 likely

document fewer than 2 percent of an estimated 3.5 million cases in 2017.

43

This analysis of EFE

SARs highlights the need for strong and diverse interventions by financial institutions, law

enforcement, and social services, as well as the involvement of policymakers.

Financial institutions are filing an increasing number of EFE SARs, but in most

cases the SARs do not indicate that they are reporting elder financial exploitation

to law enforcement or adult protective services. Fewer than one-third of EFE SARs (28

percent) say that the filing institution reported the activity to adult protective services, law

enforcement or other authorities – and only 1 percent of MSB SARs say that the filers made such

reports. If the financial institution is not reporting to adult protective services, law enforcement

or other authorities, this is a missed opportunity to strengthen prevention and response. More

reporting to the relevant law enforcement agencies can increase investigation and prosecution.

Robust reporting to APS can increase the likelihood that victims will receive appropriate

services.

EFE SARs are a useful and untapped resource for monitoring and measuring elder

financial exploitation. The information in EFE SARs sheds light on the monetary amounts at

risk, characteristics of the targeted individuals, the nature of the suspects, the types of scams

and frauds that are most common, and the types of transactions used to siphon funds from older

43

Supra note 25.

26 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

adults to bad actors. All of this information is provided through the unique lens of financial

institutions. Regular studies of the trends, patterns and issues in EFE SARs can help financial

institutions, law enforcement, service providers, and policymakers to enhance efforts to protect

older adults from financial exploitation. These entities can work independently as well as

collaboratively through community response networks.

44

The types of suspects and activities reported by money services businesses and

depository institutions differ significantly, and interventions can be tailored

accordingly. Most cases of EFE reported by MSBs are scams by strangers, while depository

institutions more often report theft by people the older adult knows and a broad array of other

financial exploitation activities. Two-thirds of suspects in depository institution filings were

people known to the older adult; in contrast, 2 percent of suspects in MSB filings were people

known to the older adult. EFE SARs involving bank accounts documented substantially higher

monetary losses than those involving money transfers. And the SARs indicate that when older

adults know the perpetrator, they lose more money than when the perpetrator is a stranger.

These patterns suggest that prevention and intervention strategies can be tailored to the types of

financial institutions where they occur and the types of perpetrators. Key stakeholders and

policymakers can read the findings and develop new responses. But some responses already

exist and can be fully and widely implemented in whichever type of institution they apply.

• Money services businesses could prevent more losses by blocking money transfers to

people who previously aroused suspicion, providing conspicuous warnings about current

scams on money transfer forms, and thoroughly training all agents, from the large chains

to the small stores. MSBs could assist victims of fraudulent activity by refunding money

transfer amounts and associated fees when appropriate and by ensuring that agents and

frontline employees are complying with anti-fraud programs and controls.

45

• Depository institutions could prevent or limit losses by improving fraud detection

technology to reflect transaction patterns most prevalent when older account holders

become victims and by using machine learning to obtain specific and timely information

44

CFPB, Report and Recommendations: Fighting Elder Financial Exploitation through Community Networks,

(Aug. 2016), available at

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/082016_cfpb_Networks_Study_Report.pdf

.

45

MSBs have agreed to implement these and other actions in consent agreements such as the 2018 agreement

between Moneygram International and the Federal Trade Commission. Supra note 26.

indicating fraudulent activity.

46

Depository institutions can promote use of alerts on

checking and savings accounts, and can offer services to enable trusted relatives and

friends to help detect elder financial exploitation.

47

Financial institutions, regulators and

policymakers could collaborate to identify and consider any changes needed to enable

depository institutions to hold transactions while investigating suspicious activity. They

might want to look at state activity in this arena. Several states allow transaction holds

when staff observe financial exploitation and report it to APS and/or law enforcement.

48

These states provide timeframes for the transaction holds and provide immunity for

institutions and employees who take these protective steps.

Law enforcement can mine the growing database of EFE SARs to be more

proactive in investigating cases and bringing more prosecutions. The database

provides law enforcement with the opportunity to access reports of a variety of suspected

financial crimes targeting older adults. Law enforcement agencies—local, state, and federal—can

mine this database to trigger new investigations and enhance ongoing inquiries. Cases can be

strengthened using important information and documentation from SARs, and the number of

prosecutions can increase.

27 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

46

CFPB, Recommendations and report for financial institutions on preventing and responding to elder financial

exploitation, (Mar 2016), available at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201603_cfpb_recommendations-and-

report-for-financial-institutions-on-preventing-and-responding-to-elder-financial-exploitation.pdf.

47

Id.

48

See, e.g., Washington (Wash. Rev. Code §74.34.215), Delaware (Del. Code Ann. tit.6 §73-307, Del. Code. Ann. tit. 31

§3910), Kentucky (Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §365.245), and Texas (Tex. Finance Code Ann. §280.004, Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat.

Ann. Art. 581, §45).

28 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX A: METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH TEAM

The research team includes Hector Ortiz, Naomi Karp, Jenefer Duane and James Miner from

the Bureau’s Office of Financial Protection for Older Americans, and Judith Ricks and Catherine

Razeto from the Bureau’s Office of Research.

DATA

The Bureau analyzed data from Suspicious Activity Reports related to elder financial

exploitation filed between April 1, 2013 and December 31, 2017. Beginning in April 2013, SAR

filers were required to use the electronic SAR form which includes a checkbox where filers can

flag the activity as elder financial exploitation. For the purposes of this study, EFE SARs were

those in which the filer selected the elder financial exploitation checkbox (field 35d) or selected

“other” under the suspicious activity category and wrote some variation of “elder” in the open

text field (fields 29z-38z). The Bureau analyzed structured data from all EFE SARs filed between

April 2013 and December 2017 to obtain the total amounts involved in suspicious activities and

the total number of filings by filer type and year.

In order to provide a meaningful description of the activities, trends and issues reported in EFE

SARs, the Bureau also relied on the analysis of a sample of 1,051 SARs, which included a review

of narratives and other unstructured data. This sample was designed to be representative of all

SARs submitted during the between April 2013 and September 2017 (95% confidence level, +-

3% confidence interval). The Bureau used the Master Activity Identifiers to draw the random

sample of EFE SARs used in this report. All related SARs in the FinCEN SAR database have a

common Master Activity Identifier. Related SARs provide information on suspicious activity

that continues (Continuing Activity SARs) or include a correction to a previous filing (Correction

SARs). Table 1 provides a comparison between EFE SARs in the random sample and all EFE

SARs filed during the same time period.

For the analysis of the random sample of EFE SARs, a group of Bureau employees with

authorized access to SARs, and with expertise in the topic of elder financial exploitation, read

these SARs and summarized each using codes. To ensure consistency in coding among team

members, the team regularly discussed, reviewed and compared each member’s coding

approach. The team analyzed the information in this sample of SARs and the codes to generate

the findings about the type of elder financial exploitation involved, the suspect’s characteristics

and relationship to the targeted individual, the targeted individual’s characteristics, types of

products and transactions involved, length of activity, whether amounts involved losses or

attempts, and whether an activity was reported to the authorities. The reading group did not

review documentation referenced in the SARs.

29 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

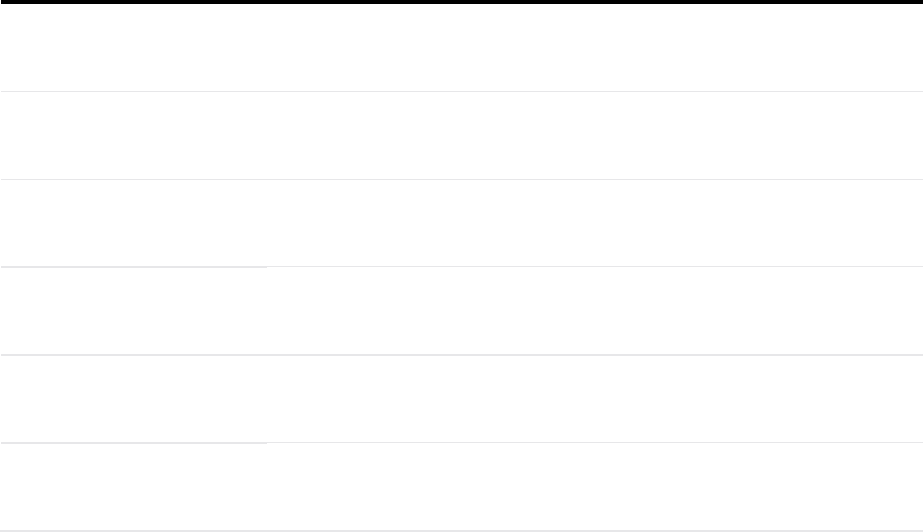

TABLE 1: COMPARISON OF RANDOM SAMPLE OF EFE SARs WITH ALL EFE SARs (APRIL 2013-

SEPTEMBER 2017)

ANALYSIS OF MONETARY AMOUNTS

Total suspicious activity amounts: To obtain the total dollar amount involved in suspicious

activities (i.e. losses and attempts), the Bureau included the dollar amounts in Continuing

Activity SARs. The Bureau excluded the top 1 percent of each year’s EFE SARs by dollar amount

involved (1,854 SARs). Excluding the top percentile is a common research technique for

correcting distortions in data due to outliers. This exclusion enabled the Bureau to study the

changes in the total amount involved over time for the remaining 99 percent of EFE SARs. A

percentile-based exclusion also prevents an unintended disclosure of a SAR (prohibited by the

Bank Secrecy Act). The excluded SARs account for a total of $142.1 billion in suspicious

activities between April 2013 and December 2017. Table 2 provides data on the number of SARs

and the amounts excluded by year.

TABLE 2: AMOUNTS EXCLUDED IN ANALYSIS OF EFE SARs BY YEAR IN MILLIONS (APRIL 2013-

DECEMBER 2017)

Year

All SARs

a

(#)

All SARs

($ in

millions)

Top 1%

(#)

Top 1%

($ in

millions)

Bottom 99%

(#)

Bottom 99%

($ in

millions)

2013

12,124

$22,013.9

122

$21,454.3

12,002

$559.6

2014 22,977 $2,157.2 230 $1,226.4 22,747 $930.7

2015

27,842

$2,225.2

279

$1,047.0

27,563

$1,178.2

2016 55,891 $103,867.6 559 $102,263.5 55,332 $1,604.1

2017

66,380

$17,791.9

664

$16,098.3

65,716

$1,693.6

Total

185,214

$148,055.8

1,854

$142,089.5

183,360

$5,966.3

Notes: (a) Includes initial filings and filings related to continuing activity.

Category

All EFE SARs

EFE SARs Sample

Total Number (Master Activity IDs)

164,446

1,051

Percent Initial Filing

92%

93%

Percent Continuing Activity Filing

6%

5%

Percent Correction Filing

3%

2%

Percent Depository Institutions

51%

50%

Percent Money Services Business

43%

44%

Percent Other

6%

6%

Percent 2013

7%

6%

Percent 2014

14%

13%

Percent 2015

16%

17%

Percent 2016

33%

33%

Percent 2017

29%

31%

Median Suspected Amount

$11,713

$12,136

30 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Average and median monetary losses: To determine whether a given amount was a loss or

a partial loss and the average loss per person/filer, the Bureau relied upon the information

provided in the random sample of SARs. The narrative portion of SARs typically provides

information about whether the amount involved represented a loss to the consumer and/or filer,

and whether all or a portion of the amounts were blocked, reversed or refunded to the consumer

(i.e. an attempt). In cases where the amounts involved may have included a combination of

losses and attempts or a combination of losses to the older adult and to the financial institution,

filers often do not provide a specific breakdown of the amounts. As a result, the average and

median loss amounts per older adult reported in this study are based on the EFE SARs where

the entire amount reported is a monetary loss to the older adult, and excludes SARs with partial

losses or any loss to the filer. All amounts reported are per targeted older adult. In 6 percent of

SARs the nature of the amounts involved and/or the person/entity sustaining a loss was unclear.

31 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX B: DETAILED TABLES

TABLE 3: NUMBER OF EFE SARs FILED PER MONTH BY FILER TYPE, INITIAL FILINGS ONLY

Year Month

Depository

Institution

Money

Services

Business

Other

All

Filers

2013

April

879

136

62

1,077

2013

May

1,015

144

75

1,234

2013

June

837

123

76

1,036

2013

July

1000

160

77

1,237

2013

August

1,077

157

71

1,305

2013

September

1,049

137

87

1,273

2013

October

1,294

381

77

1,752

2013

November

1,048

223

91

1,362

2013

December

1006

274

82

1,362

2013

Total

9,205

1,735

698

11,638

2014

January

1002

285

93

1,380

2014

February

1,072

375

93

1,540

2014

March

1,344

341

105

1,790

2014

April

1,700

430

142

2,272

2014

May

1,422

205

119

1,746

2014

June

1,358

432

106

1,896

2014

July

1,494

541

136

2,171

2014

August

1,372

486

134

1,992

2014

September

1,325

560

121

2,006

2014

October

1,463

426

124

2,013

2014

November

1,207

175

80

1,462

2014

December

1,314

264

148

1,726

2014

Total

16,073

4,520

1,401

21,994

2015

January

1,264

170

97

1,531

2015

February

1,227

258

127

1,612

2015

March

1,406

322

132

1,860

2015

April

1,461

327

160

1,948

2015

May

1,497

388

183

2,068

2015

June

1,493

383

172

2,048

2015

July

1,604

420

144

2,168

2015

August

1,474

321

174

1,969

2015

September

1,609

414

176

2,199

2015

October

1,738

543

209

2,490

2015

November

1,599

941

218

2,758

2015

December

1,661

1,635

240

3,536

2015

Total

18,033

6,122

2,032

26,187

2016

January

1,249

1,603

185

3,037

32 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Year Month

Depository

Institution

Money

Services

Business

Other

All

Filers

2016

February

1,542

1,863

177

3,582

2016

March

1,667

1,864

208

3,739

2016

April

1,703

2,005

215

3,923

2016

May

1,731

2,359

205

4,295

2016

June

1,908

2,467

235

4,610

2016

July

1,791

2,514

198

4,503

2016

August

1,859

2,811

205

4,875

2016

September

1,870

3,290

249

5,409

2016

October

1,666

3,202

237

5,105

2016

November

1,749

3,077

260

5,086

2016

December

1,761

3,202

236

5,199

2016

Total

20,496

30,257

2,610

53,363

2017

January

1,573

3,403

206

5,182

2017

February

1,631

2,859

213

4,703

2017

March

2,003

3,663

283

5,949

2017

April

1,900

2,645

211

4,756

2017

May

1,865

3,281

365

5,511

2017

June

1,852

3,227

433

5,512

2017

July

1,729

2,437

468

4,634

2017

August

1,915

3,506

464

5,885

2017

September

1,829

3,116

450

5,395

2017

October

1,917

3,462

497

5,876

2017

November

2,040

2,517

547

5,104

2017

December

1,739

2,662

600

5,001

2017

Total

21,993

36,778

4,737

63,508

2013 - 2017

Total

85,800

79,412

11,478

176,690

33 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

TABLE 4: SUSPECTED AMOUNTS REPORTED IN INITIAL AND CONTINUING ACTIVITY EFE SARs BY

QUARTER AND FILER TYPE (IN MILLIONS)

Year/Quarter

DI

MSB

Other

Total

2013 Q2

$137.9

$4.8

$22.5

$165.1

2013 Q3

$159.8

$5.7

$25.5

$190.9

2013 Q4

$172.2

$10.7

$20.6

$203.5

Total 2013

$469.9

$21.2

$68.6

$559.5

2014 Q1

$154.0

$10.0

$25.7

$189.7

2014 Q2

$199.3

$14.1

$32.4

$245.8

2014 Q3

$205.0

$15.3

$32.7

$253.0

2014 Q4

$201.1

$10.1

$31.0

$242.2

Total 2014

$759.4

$49.5

$121.8

$930.7

2015 Q1

$191.2

$12.9

$28.0

$232.1

2015 Q2

$226.6

$22.0

$37.4

$286.1

2015 Q3

$237.5

$22.0

$38.7

$298.3

2015 Q4

$261.0

$47.6

$53.1

$361.7

Total 2015

$916.3

$104.5

$157.2

$1,178.2

2016 Q1

$219.4

$77.6

$36.7

$333.7

2016 Q2

$262.1

$94.5

$48.8

$405.4

2016 Q3

$277.2

$112.8

$43.5

$433.5

2016 Q4

$254.6

$125.3

$51.7

$431.5

Total 2016

$1,013.3

$410.2

$180.7

$1,604.1

2017 Q1

$243.7

$130.2

$50.2

$424.1

2017 Q2

$269.3

$80.7

$63.9

$413.9

2017 Q3

$264.1

$76.4

$84.4

$425.0

2017 Q4

$270.9

$59.7

$100.1

$430.7

Total 2017

$1,048.0

$347.0

$298.6

$1,693.7

Total

$4,206.9

$932.5

$826.8

$5,966.3

34 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX C: BUREAU INITIATIVES TO HELP

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS FIGHT ELDER

FINANCIAL EXPLOITATION

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (Bureau) has provided regulatory guidance,

voluntary recommendations, and other materials to assist financial institutions in preventing

and responding to elder financial exploitation. These actions include:

Memorandum on financial institution and law enforcement efforts to combat

elder financial exploitation (August 2017)

Joint memorandum on financial institution and law enforcement efforts to combat elder

financial exploitation, issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, FinCEN and the Bureau.

The purpose of the memorandum is to encourage coordination among financial institutions, law

enforcement and adult protective services agencies in order to protect older adults from

financial abuse.

consumerfinance.gov/policy-compliance/guidance/implementation-guidance/memorandum-

financial-institution-and-law-enforcement-efforts-combat-elder-financial-exploitation/

Recommendations and report for financial institutions on preventing and

responding to elder financial exploitation (March 2016)

Report/Recommendations for financial institutions on preventing and responding to elder

financial exploitation. This report presents a set of voluntary recommendations released in

March 2016 to assist banks and credit unions with their efforts to prevent elder financial abuse

and intervene effectively when it occurs.

consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/recommendations-and-report-financial-

institutions-preventing-and-responding-elder-financial-exploitation/

Interagency Guidance on Privacy Laws and Reporting Financial Abuse of Older

Adults (September 2013)

Interagency guidance on privacy laws and reporting financial abuse of older adults, issued in

September 2013 by the Bureau and seven other federal financial regulators. The Guidance

clarifies that reporting financial abuse of older adults to appropriate authorities does not, in

general, violate the privacy provisions of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

consumerfinance.gov/policy-compliance/guidance/implementation-guidance/interagency-

guidance-reporting-financial-abuse-older-adults/

35 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX D: GLOSSARY

Terms

BSA

Bank Secrecy Act

DI

Depository Institution

EFE

Elder financial exploitation

FinCEN

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

MSB

Money Services Business

SAR

Suspicious Activity Report